813.876.3636

813.876.3636

A thyroid nodule is a lump in or on the thyroid gland, located in the lower front of the neck. Thyroid nodules are common but often go undiagnosed. They are found in about six percent of women and one to two percent of men, becoming more common with age. While the majority of thyroid nodules are benign, the possibility of cancer must always be considered.

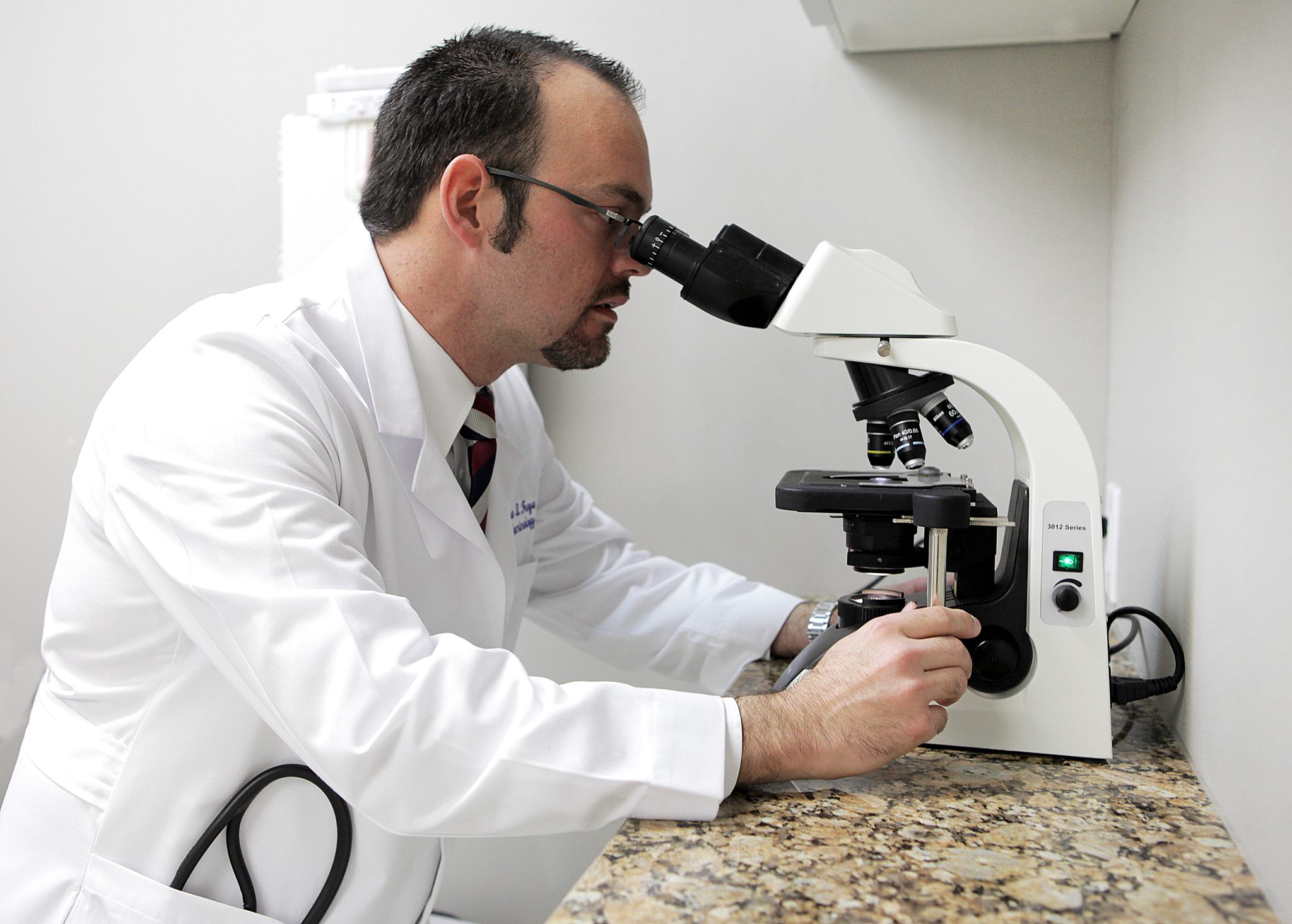

1. Thyroid Needle Biopsy: A thyroid fine needle biopsy involves extracting tissue from the nodule using a thin needle. This minimally invasive procedure provides detailed information, often eliminating the need for surgery. Ultrasound guidance and molecular testing enhance diagnostic accuracy.

2. Thyroid Scan :A thyroid scan uses a radioactive isotope to image the thyroid gland, identifying nodules as hot (hyperfunctioning), warm (normal), or cold (nonfunctioning). Hot nodules rarely indicate cancer. This test helps guide treatment, especially for hyperthyroidism.

3. Thyroid Ultrasonography: Thyroid ultrasonography uses high-frequency sound waves to create detailed images of the thyroid gland, distinguishing between cystic and solid nodules. It guides fine needle biopsies and monitors nodule size, improving diagnostic accuracy and patient care.

Treatment depends on the characteristics of the nodule:

Regular follow-up with an experienced physician is important for monitoring thyroid nodules and ensuring appropriate management.

Our Endocrinologists, Dr. Carlo A. Fumero, Sean Amirzadeh, DO, Alberto Garcia Mendez, Lauren Sosdorf, and Pedro Troya, are board certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine and have a wealth of experience treating thyroid conditions. They will work with you to create a personalized treatment plan that meets your unique needs.

Tampa Office:

Zephyrhills Office:

Plant City Office: