813.876.3636

813.876.3636

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, also known as autoimmune or chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, is the most prevalent thyroid disease in the United States. Affecting approximately 14 million Americans, it is about seven times more common in women than in men. This inherited condition is characterized by the body’s immune system producing cells and autoantibodies that attack and damage thyroid cells, impairing their ability to produce thyroid hormone. If the thyroid hormone production is insufficient, hypothyroidism occurs. The thyroid gland may also enlarge, forming a goiter.

Early Stages:

When Symptoms Appear:

Systemic Symptoms of Hypothyroidism:

Progression:

The condition results from an immune system malfunction. Normally, the immune system protects the body against foreign invaders like bacteria and viruses. In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, the immune system mistakenly targets normal thyroid cells, producing antibodies that destroy these cells. Despite extensive research, no environmental factors have been definitively proven to cause Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

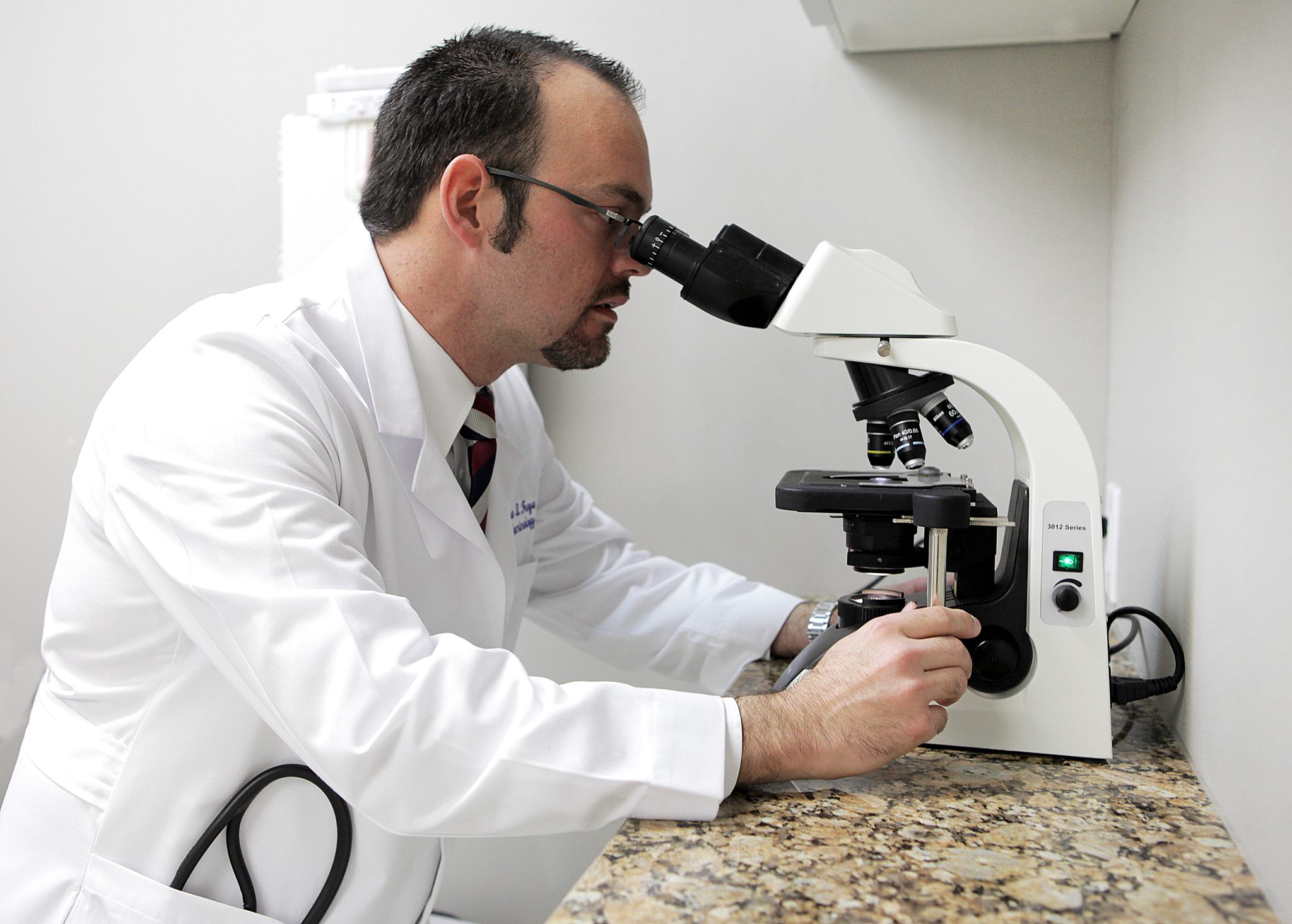

Physical Examination: A physician can detect goiter and hypothyroidism through characteristic symptoms, physical signs, and appropriate laboratory tests.

Laboratory Tests:

Thyroid Hormone Therapy:

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis can increase the risk of other autoimmune conditions due to a malfunctioning immune system, which may affect various parts of the body. These include:

Management

Effective management requires ongoing care by a physician experienced in treating Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. This includes monitoring and adjusting thyroid hormone levels and addressing any associated autoimmune conditions to ensure optimal health outcomes.

Our Endocrinologists, Dr. Carlo A. Fumero, Sean Amirzadeh, DO, Alberto Garcia Mendez, Lauren Sosdorf, and Pedro Troya, are board certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine and have a wealth of experience treating thyroid conditions. They will work with you to create a personalized treatment plan that meets your unique needs.

Tampa Office:

Zephyrhills Office:

Plant City Office: